The BBC series A History of the World in 100 Objects uses a photograph of a bronze statue of Minoan bull-leaping as one of its promotional images.

BBC promotional photograph. (British Museum)

This bronze figurine depicts a man somersaulting over a bull. It comes from the island of Crete and was probably used in a shrine or a cave sanctuary. Bulls were the largest animals on Crete and were of great social significance. Bull jumping was probably performed during religious ceremonies, although a leap such as this would have been almost impossible.

Read about bull-leaping and bronzes here:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/eU0DV7kOQ5inxmklD__YIw

Minoan bull leaping. Fresco, Palace of Knossos, Crete. 17th-15th Century, BCE.

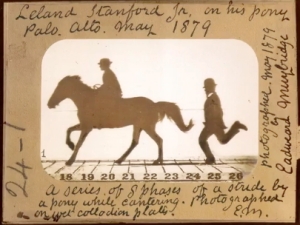

Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope subjects included a scene of a man somersaulting over a bull, created by combining photographic sequences in his painted creation.

…Mr. Muybridge has succeeded in combining a series of movements which make a very laughable picture. A man is running with a wild bull in close pursuit. After the bull comes a greyhound, and just as the infuriated bovine reaches the man, he throws a back somersault, striking the ground behind both, while the dog seems ready to catch the bull by the tail … It is so realistic that were it possible to do such a feat it could not be more so.

Spirit of the Times (California) 27 March 1880.

Muybridge described this combination technique in his Preface to the 1899 Animals in Motion, but it has been almost completely overlooked or ignored by historians.

(c) Kingston Museum. Reproduced with permission.

Muybridge’s interpretation, based on combining three motion sequences – athlete, bull, and dog.

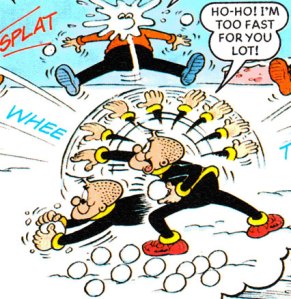

It’s often suggested that Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope was a brave but failed attempt at cinematography – partly because he projected painted silhouettes informed by the camera, rather than actual photographs. But his technique was more versatile than simply reproducing photographs in sequence on a screen – his projector much more than a primitive cinematograph.

His zoopraxiscopical production method could show a simple silhouette sequence to prove the validity of the individual poses (such graphic representations are today computer-generated), but allowed for far greater imaginative interpretation than a basic series of photographs in motion would have done. In particular, it made possible combined sequences in a single scene – as the “bull-leaping” example demonstrates. Without these combinations there would have been no “Rotten Row” horse scene, no flock of birds flying, no “Three men racing”. Muybridge’s intuition that his Zoopraxiscope method was – for him – the way to go was vindicated by its widely acclaimed reception.

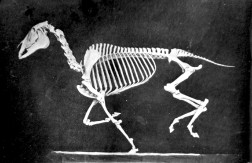

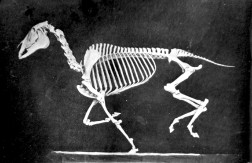

Horse skeleton photograph – before manipulation for Zoopraxiscope

(c) Kingston Museum. Reproduced here with permission.

And although it was to be fifteen years after the Zoogyroscope debut before anyone would screen actual animated photo sequences taken in real time (Anschutz’s electrical tachyscope projection model, double disc maltese cross, 1894), in fact the Zoogyroscope/Zoopraxiscope COULD animate photographs – and did, with the posed skeleton horse sequence. It was a fiddly, difficult process – for technical reasons each image had to be ‘stretched’ in a particular way to overcome image compression when projected – but Muybridge proved that this could be done with actual photographs. He did it for this one disc only – because for once, he needed to animate a detailed photo sequence.

But Muybridge’s ambitions were clearly elsewhere – with his painted silhouette combinations. Then, much later and under pressure to get new material for the World’s Fair at Chicago, he took a wrong turning, trying to add colour while retaining his flexible image-combination technique. He was no doubt aware that Edison (and indeed Ottomar Anschutz) planned to have moving photos in peepboxes at the fair, and was trying to do something different from just animating photographs – he wanted to create a herd of galloping buffalo from his photo sequence of one lone animal, add a turbaned rider to his elephant, create a Chicago horse race from several galloping horse sequences and an imagined crowd of matchstick-men – ‘cartoon’ images manipulated and extrapolated from his existing photo negatives. And remember, even then (1892-3) NO ONE ELSE had projected ordinary animated photographs, either* – so for Muybridge to do this as a straightforward production method (i.e. without having to create the specially distorted photographic positives necessary for his Zoopraxiscope), a newly invented machine and a period of experimentation would have been necessary – and he didn’t have the time, or the team.

It seems that Muybridge never did show the later Zoopraxiscope discs of coloured drawings. He rejected them as being a step too far from his published series photographs, by which he wished to be remembered.

[* Note: The 1870s Heyl’s Phasmatrope probably only worked at around 3 fps, so would not have been suitable, and I’m not convinced the 1892 Demeny disc machine could usefully project onto a large screen.]

More on Muybridge’s motion discs here.

http://www.stephenherbert.co.uk/muy%20blog.htm#part24

and here:

http://www.stephenherbert.co.uk/muy%20blog3.htm#part15

A detailed account of Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope and his lectures, Projecting the Living Image, is in: Eadweard Muybridge. The Kingston Museum Bequest (Kingston Museum / The Projection Box 2004). Details (and more Zoopraxiscope pictures) here.

Copyright. Not to be reproduced.

Copyright. Not to be reproduced.

Even before Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope presentations, some very impressive animations of animals in motion had been produced by others. The Irish artist Michael Angelo Hayes (1820-1877) was responsible for this extraordinary scene for the phenakistiscope. More about Hayes and his unique motion discs another time.